Social Game Design: Party Edition

A case study in social dynamics, and games that occur outside the computer.

When I was a kid, my birthday was always during the state championships for hockey, so as a result, I never got to have birthday parties, not proper ones. So when I grew up, I went hard in the other direction and went absolutely HAM making the greatest parties I could imagine. They were legendary, and people hung out for what the concept was going to be every year.

One year, there was a Nintendo party where I got a heap of old consoles and emulators and set them up all over the house, something like 10 screens in total, everyone came in costume of their favorite Nintendo characters. Another year, I ran a mini-festival, invited four bands, and after they played their sets, they started taking requests. “Who knows [such and such a song]” and people from various bands would jump on whatever instrument and try to play it from memory.

If these seem like they have divergent audiences, it’s because they did. I had my friends who played video games and tabletop, my music friends who played in bands, and my work friends who were all network engineers, and I noticed that even in these party situations, the groups rarely interacted with each other.

That’s what sparked the idea for a social game party that would encourage them to mix.

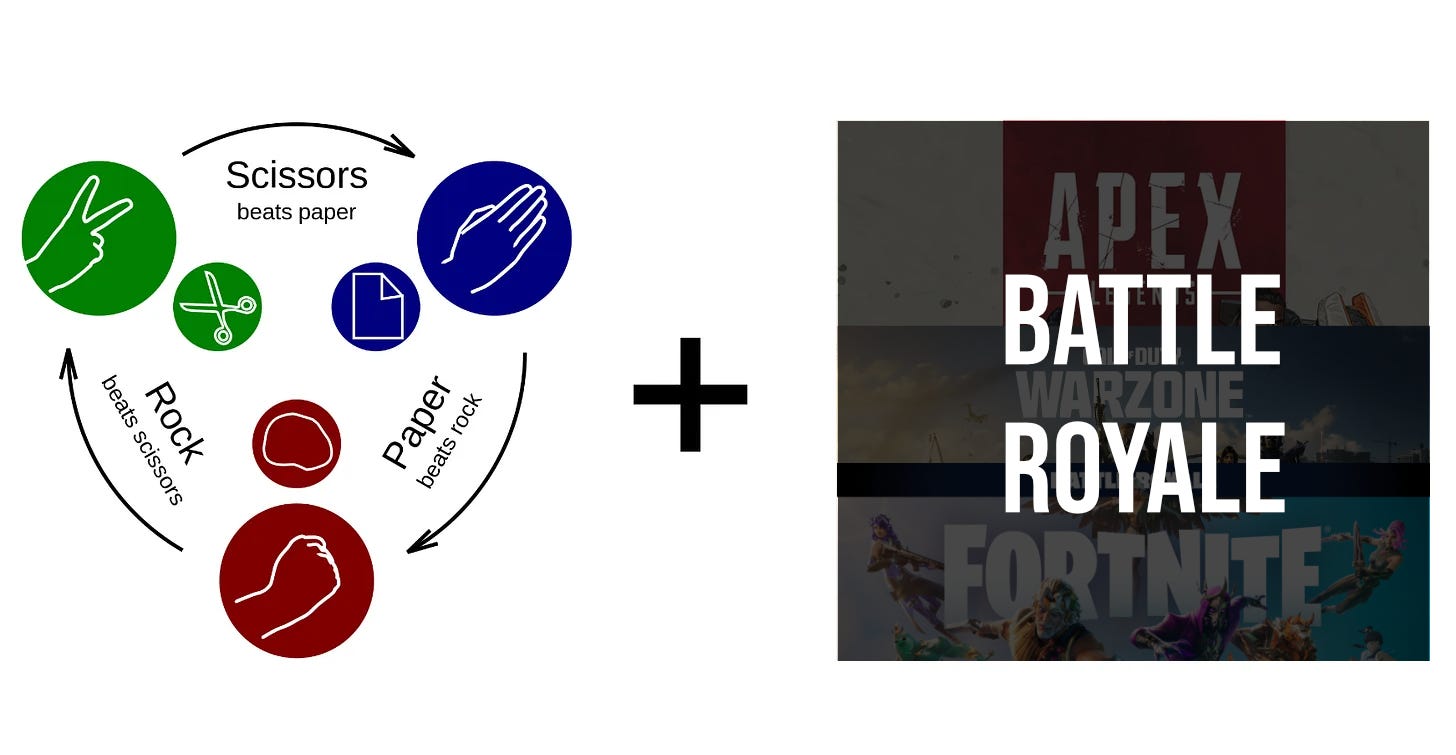

A Social Rock-Paper-Scissors Battle Royale

I made hundreds of badges, each with a picture of either Rock, Paper, or Scissors, and put them in buckets behind a desk by the door. As people arrived, they were issued three badges, either Rock, Paper, or Scissors.

The rules were simple:

You may challenge someone with a badge that your badge “beats” to a game of Rock Paper Scissors.

You “bet” your badge against your opponent’s badge.

Best of three wins the opponent’s badge.

A challenge could not be refused.

The beaten party could request a rematch, but had to bet double the previous bet ie. playing for two badges.

A rematch request could be refused.

Any type of badge could be bet on a rematch.

This could continue to happen as long as people wanted, each time doubling the number of badges on the line.

The winner would be the person with the most badges at the end of the night.

The Twist

This is where it got sneaky.

When you started, you got three badges of the same type. By selectively weighting which types of badges were distributed to people from which social circle, I was able to make it so that while it was possible to play a little within your own group, you needed to go outside it to get a lot of matches. This worked exactly how I’d imagined - groups played within themselves at first, but quickly found themselves exhausting their pool, and looked for more opponents. The groups began to mix, and the previously disparate social groups drank, competed, and bet more and more against each other.

If you lost all your badges and wanted to keep playing, you could request more from the secret stash behind the counter.

The Outcome

By the end of the night, all of the reserve badges were gone, and almost all the badges were concentrated on two people, creating a massive grand final surrounded by drunken cheering, and both went all-in on one final best-of-three.

I don’t remember who won. It wasn’t important. What was important was that the design of the game was explicitly crafted around affecting player behavior to influence movement around the house and which other players they interacted with. When it was over, we did what we did at the end of every party and fell back to the one activity that sated every ground: playing Rock Band on a full suite of instruments.

It was a success by every metric. By the end of the night, the badges were ALL gone, everyone had played the maximum amount possible and aside from the badges people stole for posterity, the game ended with no-one else able to challenge the winner.

That night formed many new friendships (and a few hookups 😘) and represented a major social shift in the social makeup of the groups. The music crew and the gaming crew partially merged and began to hang out outside of my gatherings. The tech crew didn’t integrate as well, but did have some fringe overlap with the gaming crew, and that also formed some new friendships. The more introverted folks took more time to join the fray than others, but after a few drinks and a few matches, still mingled outside of their circles, which didn’t usually happen.

The Retro

This was a rousing success, but that doesn’t mean there weren’t lessons to be learned. I retro’d this, because of course I did, to see what I could have done better, and figured out a few missed opportunities.

Learned: People had a bias towards which badge they wanted to start with.

This makes sense as most people default to a particular move in RPS.

Do differently (Art): I could have influenced this by doing better badge design to appeal to each intended group e.g. album-art themed for scissors for music, D&D themed for rock, tech-themed for paper.

Went poorly: There were not enough snacks.

Do differently (MTX): I could have encouraged people to bring snacks by offering snack tokens to exchange for additional badges, which people wanted.

This would require getting something previously unavailable so perhaps needed to add a time gate like ‘no replacement badges in the first hour except for via snack token’.

That would need to feel optional so as not to appear greedy or demanding.

Learned (via Feedback): The idea of not being able to refuse a challenge made some of the more introverted people uncomfortable, but ultimately they came to enjoy it.

This was primarily a perception issue but could have been a trust & safety issue if I had less trustworthy friends.

Fortunately everyone was reasonably socially competent so they tended not to bother people who didn’t want to be bothered.

Do differently (Social): I needed a mechanism via which people could set themselves to be ‘off the table’ for challenges.

Perhaps ‘visible badges’ and you could hide them with a coat?

Brisbane winter is cold enough that indoor coat usage is viable.

Alternately, a flippable state badge for red/green. This would have required more effort and for me to start this process more than two days before the event.

How This Applies To Game Development

Wherever you go, the sky is the sky and people are people.

Changing the method of the game adjusts your tooling. When designing physical games, you no longer have a computer to track state and enforce rules. Instead, state is tracked physically and rules are enforced cognitively. Both of these things create player burden.

A game for drunk people in a social setting needed to have rules that were trivial to enforce, and state that was trivial to track. The known mechanics of Rock-Paper-Scissors required no learning, so there were only two new systems for players to learn:

Matchmaking

Progression

When designing player-facing game systems, you have to think through how players are going to:

Interpret what they’ve been presented with

Think using that interpretation

Feel about that interpretation

Act based on those thoughts and feelings

I call this “human state machine modeling”, and it relies on the fundamentals of how people experience things to create experiences. It’s the fundamental way that I approach design, and it applies to everything from game design to copywriting to internal process design.

Stay tuned for a deep dive into that in a future post here on Load-bearing Tomato.

The future delivered: “How People Experience Things.”

// for those we have lost

// for those we can yet save